Pituffik Glacier is one of Greenland’s many magnificent glaciers. It is situated in the Thule region at latitude 76 degrees north, only about 30 kilometres from Thule Air Base and just over 1,200 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle.

Text: Mads Nordlund, greenland today November 2015

On this beautiful August evening a small, privileged group of us are sailing from Thule Air Base towards the glacier. I feel fortunate, because very few people get this opportunity. Only a few of those who work on the base get to go sailing because it means you have to have a boat or you have to know someone who does. A boat is probably not the first thing that crosses your mind when you are employed on a temporary contract in a place where the sailing season lasts just a few months. It is different for the resident hunters in the surrounding villages who need their boats for hunting. Not many tourists drop by either. Only a few cruise companies end the summer season by sailing so far to the north of Greenland.

Rich wildlife

The water is calm, almost dead calm, when we round the headland at Thule Air Base. There is a view of flat-topped Mt. Dundas on the right and Saunders Island right ahead. Flocks of guillemots and black guillemots sweep all around the boat close to the surface of the water. They breed in millions in the summer in what the biologists call North Water or the Arctic Ocean. Here, there is plenty for them to feed on. The minerals released from the melting ice attract both krill and plankton which are eaten by the smaller fish, the primary food of the guillemots.

On the way, a seal sticks its head up as if to check that tourists are really here. It is not shy and takes its time to study us before it swims on.

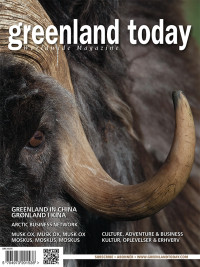

On the approach to Pituffik Glacier you pass Kangilinnguit, which is appropriately called Green Valley in English. Even from the water it is clear to see how green it is on land and down to-wards the beach about 40 musk-oxen and their calves are grazing.

In their eagerness to get to the greenest grass, a couple of them have climbed up the steep rocks. It is easy to understand that musk-oxen are related more closely to goats than cattle when you see their ability to climb.

In spite of the harsh winters in this region, with extremely high winds and frost down to minus 40 degrees, the musk-ox population in the region has been growing for many years, according to the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources. An increase in the frequency of polar bears has also been observed in the area, possibly as a result of the cooperation between the Arctic countries which includes limitations on hunting.

Impressive ice

Although the glacier calves many icebergs, it is far from being one of the most productive glaciers, partly because of the short season with open water at these latitudes. The amount of icebergs, growlers and brash ice increases as the boat gets closer to the huge face of the Pituffik Glacier. The captain slows down to avoid the growlers and it is not possible to sail very close to the glacier for safety reasons, so he keeps the boat at a few hundred meters’ distance while the guests busy themselves with their cameras on the ship’s aft deck.

The ice face stretches many hundreds of metres up from the surface of the water and behind it tons of ice push forward to come out and break away as newly-calved icebergs. It is an enthralling sight – a one-kilometre long vertical wall of ice with fissures that give the wall of ice structure and enable us to discern individual vertical cracks from the rest, which is otherwise white on white.

As I landed a few days ago, I saw the glacier from the air. Here, it was clear to see how the ice cap almost flows out towards the glacier and makes several folds in large curves as it fills with more and more cracks and crevices, approaching the face where the ice breaks off.

I stand on the aft deck with the others. Although the glacier face is several hundred metres away, you can clearly feel the extreme cold which is like an invisible force that flows towards us from the glacier. Regardless of attire, it soon feels very cold.

On the way back, the captain sails as close to the icebergs as possible, but still at a safe distance. Just as everyone has focused their cameras on yet another colossal iceberg, large pieces start to break off and the iceberg tips and tilts several degrees before it gains its balance again. This is why you must keep your distance and although it comes as no surprise that the iceberg tilts, it is surprising that we are able to witness it at such close quarters.

For the rest of the trip I am on the look-out for whales and seals, but apart from the birds, there are no more animals that evening. Nevertheless, I am sated after yet another magnificent experience in the nature of North Greenland and exceedingly thankful to have had an opportunity to visit one of Greenland’s least visited glaciers.